If GPUs Are So Good, Why Do We Still Use CPUs At All?

There’s this old video from 2009 that’s been going viral on Twitter recently. Its supposed to give viewers an intuition of the difference between CPUs and GPUs.

You can watch it here, it’s 90 seconds long:

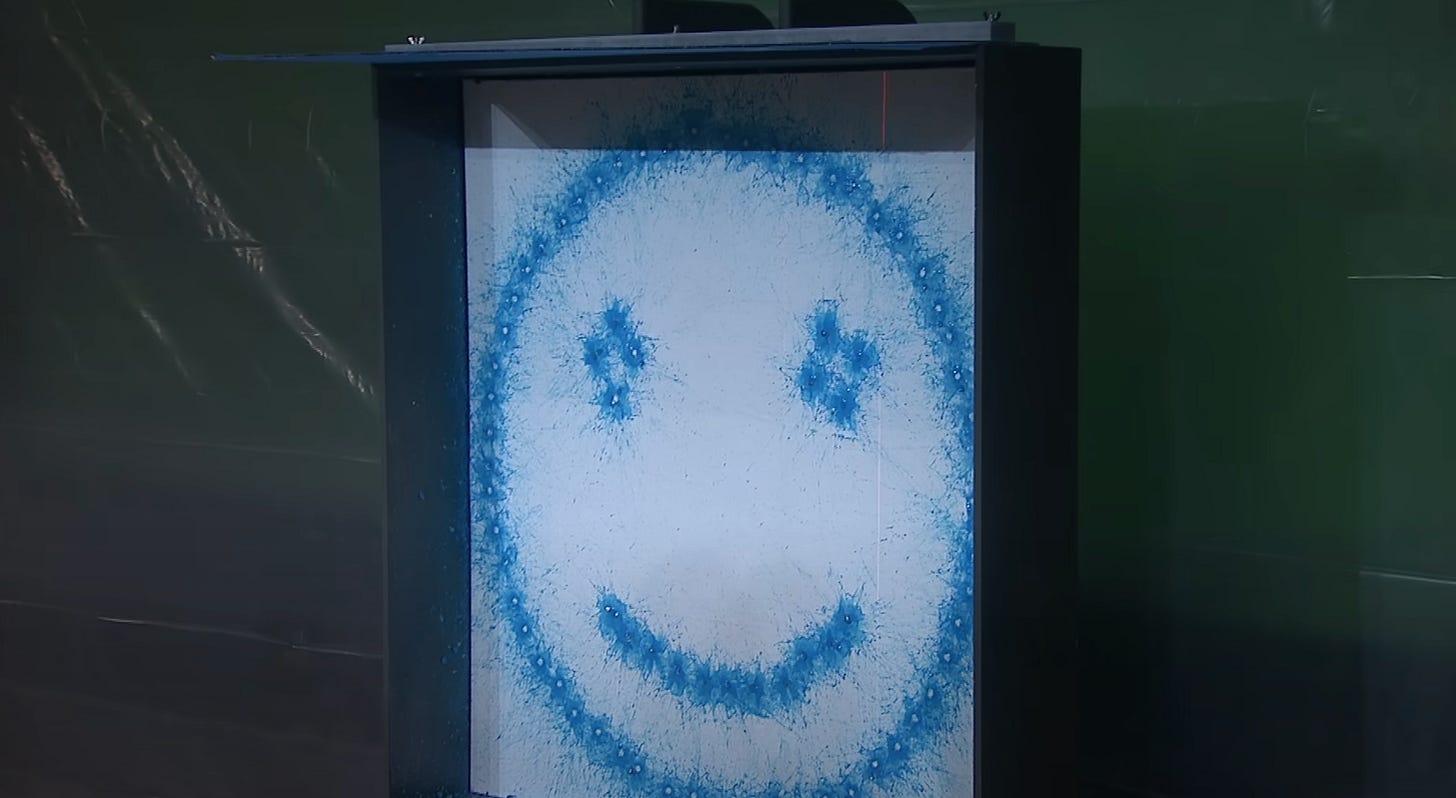

The idea is that a CPU and a GPU go to head-to-head in a painting duel. The processors are hooked up to a machine that shoot paintballs.

The CPU takes a full 30 seconds to paint a very basic smiley face:

And then the GPU paints the Mona Lisa in an instant:

One takeaway from this video: CPUs are slow and GPUs are fast. While this is true, there’s a lot more nuance that the video doesn’t give.

Tera Floating Point Operations Per Second (TFLOPS)

When we say GPUs are much more performant than CPUs, we’re talking about a measurement called TFLOPS, which essentially measures how many trillions of mathematical operations a processor can do in a second. For example, the Nvidia A100 GPU can do 9.7 TFLOPS (9.7 trillion operations per second) while the recent Intel 24-core processor can do 0.33 TFLOPS. That means a middle-of-the-road GPU is at least 30x faster than even the most capable CPU.

But the chip in my MacBook (Apple M3 chip) contains a CPU and a GPU. Why? Can’t we just do away with these terribly slow CPUs?

Different Types of Programs

Let’s define two types of programs: sequential programs and parallel programs.

Sequential Programs

Sequential programs are programs where all the instructions have to run one-after-another. Here’s an example.

def sequential_calculation():

a = 0

b = 1

for _ in range(100):

a, b = b, a + b

return bHere, 100 times in a row, we calculate the next number using the previous two numbers. The important quality of this program is that each step depends on the two steps before it. If you were doing this calculation by hand, you couldn't tell a friend, "You calculate steps 51 through 100 while I start from step 1" because they would need the results of steps 49 and 50 to even begin calculating step 51. Each step requires knowing the previous two numbers in the sequence.

Parallel Programs

Parallel programs are programs where multiple instructions can be executed simultaneously because they don't depend on each other's results. Here's an example:

def parallel_multiply():

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

results = []

for n in numbers:

results.append(n * 2)

return resultsIn this case, we do ten multiplications that are totally independent of each other. The important thing is that the order doesn’t matter. If you wanted to split the work with a friend, you could say, “You multiply the odd numbers while I multiply the even numbers.” You could work separately and simultaneously and get an accurate result.

A False Dichotomy

In reality, this divide is a false dichotomy. Most large real-world applications contain a mix of sequential and parallel code. In fact, every program will have a percentage of its instructions that are parallelizeable.

For example, lets say we have a program that runs 20 calculations. The first 10 are Fibonacci numbers that must be calculated in sequence, but the later 10 calculations can be run in parallel. We would say this program is "50% parallelizeable" because half the instructions can be done independently. To illustrate this:

def half_parallelizeable():

# Part 1: Sequential Fibonacci calculation

a, b = 0, 1

fibonacci_list = [a, b]

for _ in range(8): # Calculate 8 more numbers

a, b = b, a + b

fibonacci_list.append(b)

# Part 2: Each step is independent

parallel_results = []

for n in fibonacci_list:

parallel_results.append(n * 2)

return fibonacci_list, parallel_resultsThe first half must be sequential - each Fibonacci number depends on the two numbers before it. But the second half can take that completed list and double each number independently.

You couldn't calculate the 8th Fibonacci number without first calculating the 6th and 7th numbers, but once you have the full sequence, you could distribute the doubling operations across as many workers as you have available.

Different Processors For Different Program Types

Broadly speaking, CPUs are better for sequential programs and GPUs are better for parallel programs. This is because of a fundamental design difference in CPUs and GPUs.

CPUs have a small number of large cores (Apple’s M3 has an 8-core CPU), and GPUs have many small cores (Nvidia’s H100 GPU has thousands of cores).

This is why GPUs are great at running highly parallel programs - they have thousands of simple cores that can perform the same operation on different pieces of data simultaneously.

Rendering video game graphics is an application where many simple repetitive calculations are required. Imagine your video game screen as a giant matrix of pixels. When you suddenly turn your character to the right, all the those pixels need to be recalculated to new color values. Luckily, the calculation for the pixels at the top of the screen are independent from the pixels at the bottom of the screen. So the calculations can be split across the many thousands of cores of GPUs. This is why GPUs are so crucial for gaming.

CPUs Are Good At Handling Random Events

CPUs are much slower than GPUs at highly parallel tasks like multiplying a matrix of 10,000 independent numbers. However, they excel at sophisticated sequential processing and complex decision-making.

Think of a CPU core as a head chef in a busy restaurant kitchen. This chef can:

Instantly adapt their cooking plan when a VIP guest arrives with special dietary requirements

Seamlessly switch between preparing a delicate sauce and checking on roasting vegetables

Handle unexpected situations like a power outage by reorganizing the entire kitchen workflow

Orchestrate multiple dishes so they all arrive hot and fresh at exactly the right moment

Maintain food quality while juggling dozens of orders in different states of completion

In contrast, GPU cores are like a hundred line cooks who excel at repetitive tasks - they can chop an onion in two seconds, but they can't effectively run the whole kitchen. If you asked a GPU to handle the constantly changing demands of a dinner service, it would struggle.

This is why CPUs are crucial for running your computer’s operating system. Modern computers face a constant stream of unpredictable events: apps starting and stopping, network connections dropping, files being accessed, and users clicking randomly across the screen. The CPU excels at juggling all these tasks while maintaining system responsiveness. It can instantly switch from helping Chrome render a webpage to processing a Zoom video call to handling a new USB device connection - all while keeping track of system resources and ensuring every application gets its fair share of attention.

So while GPUs excel at parallel processing, CPUs are still essential for their unique ability to handle complex logic and adapt to changing conditions. Modern chips like Apple's M3 have both: combining CPU flexibility with GPU computing power.

In fact, a more accurate version of the painting video would show the CPU managing the image download and memory allocation, before dispatching the GPU to rapidly render the pixels.

> you couldn’t tell a friend, “You calculate steps 1 through 50 while I calculate steps 51 through 100.” Because you would both need to have run all steps in order to get an accurate result.

Not true for this example? The order in which you multiply numbers doesn't affect the result, so we're free to split the steps and then multiply our answers together for the final result.